Case Study 10

Axe 5

Objet d'étude 2

Myth makeover

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Imagine a modern retelling of a classic Greek myth.

The classic Greek myths have been told and retold for centuries, yet they remain a powerful source of inspiration for modern creators. Whether through books, films, or comics, these ancient stories continue to find new life. Now, it's your turn! You will reimagine a famous Greek myth, putting your own creative spin on a timeless legend.

The classic Greek myths have been told and retold for centuries, yet they remain a powerful source of inspiration for modern creators. Whether through books, films, or comics, these ancient stories continue to find new life. Now, it's your turn! You will reimagine a famous Greek myth, putting your own creative spin on a timeless legend.

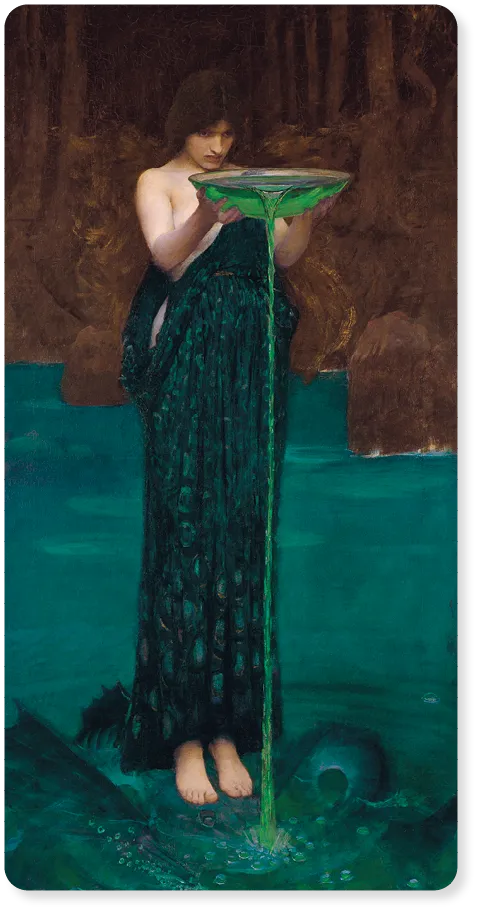

J. W. Waterhouse, Circe Invidiosa, 1892.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Circe is often referred to as the first sorceress. She is the daughter of the sun of god Helios and the Oceanid nymph Perse. She's able to transform humans into animals.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

1The enduring power of Greek myths

The enduring power of Greek myths

Among my most treasured books as a child was a volume of Greek myths. [...] It infiltrated my childhood imagination – it was one of the things that set me on the path to studying classics, and becoming a writer. The stories were strange and wild, full of powerful witches, unpredictable gods and sword-wielding slayers. They were also extreme: about families who turn murderously on each other; impossible tasks set by cruel kings; love that goes wrong; wars and journeys and terrible loss. There was magic, there was shapeshifting, there were monsters, there were descents to the land of the dead. Humans and immortals inhabited the same world, which was sometimes perilous, sometimes exciting. The stories were obviously fantastical.

All the same, brothers really do war with each other. People tell the truth bur aren't believed. Wars destroy the innocent. Lovers are parted. [...] Floods and fire tear lives apart. [...] Greek myths remain true for us because they excavate the very extremes of human experience: sudden, inexplicable catastrophe; radical reversals of fortune; seemingly arbitrary events that transform lives. They deal, in short, in the hard basic facts of the human condition. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, myths were everywhere. [...]

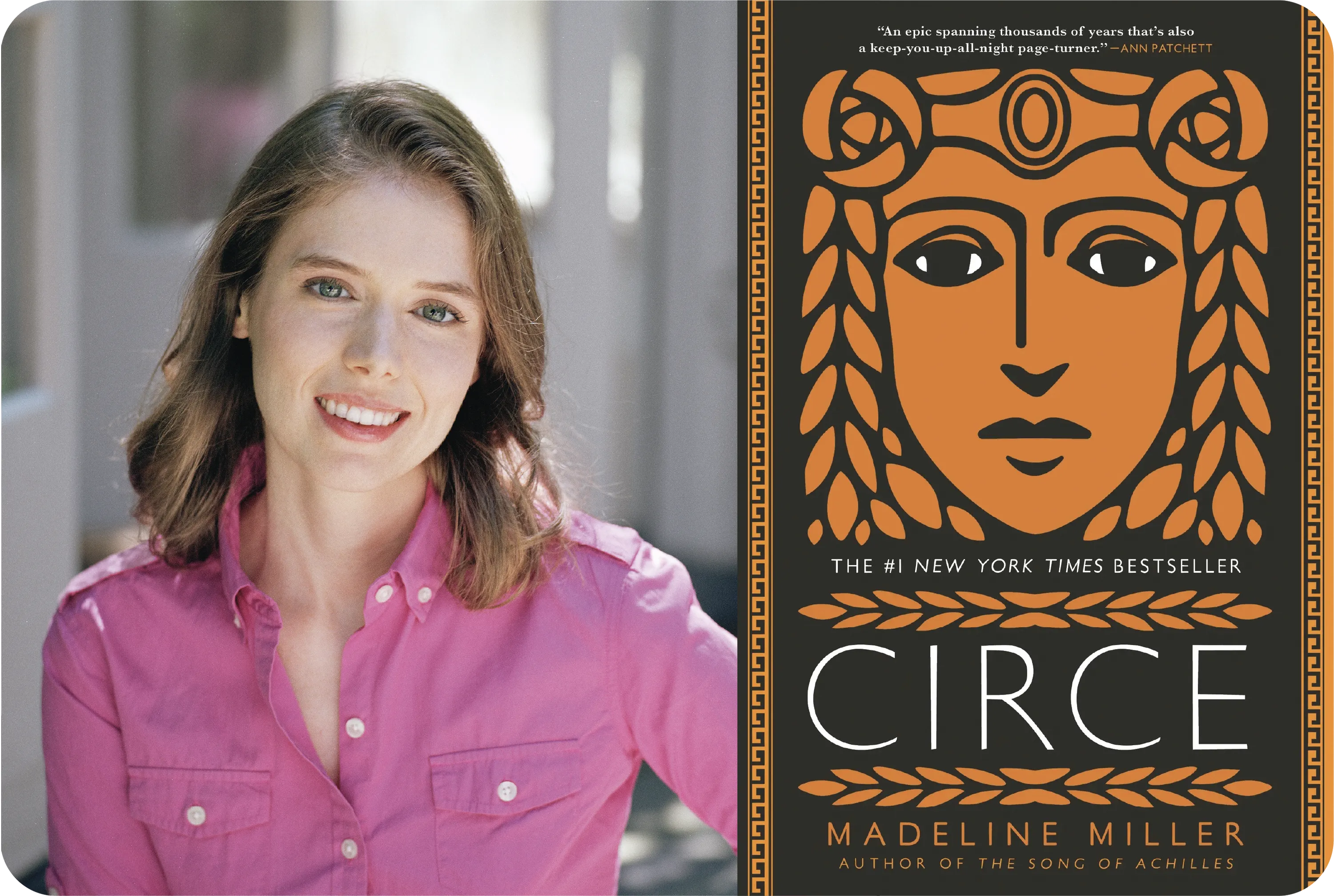

Some of the flattening-down of the strangeness and violence of the characters of classical literature has doubtless been an understandable consequence of retelling the tales with children in mind. But the Greek myths shouldn't be thought of as children's stories – or just as children's stories. In some ways, they are the most grownup stories I know. In recent years there has been a blossoming of novels – among them Par Barker's The Silence of the Girls, Natalie Haynes's A Thousand Ships and Madeline Miller's Circe – that have placed female mythological characters at the centre of stories to which they have often been regarded as peripheral. [...] Once activated by a fresh imagination, the stories burst into fresh life.

All the same, brothers really do war with each other. People tell the truth bur aren't believed. Wars destroy the innocent. Lovers are parted. [...] Floods and fire tear lives apart. [...] Greek myths remain true for us because they excavate the very extremes of human experience: sudden, inexplicable catastrophe; radical reversals of fortune; seemingly arbitrary events that transform lives. They deal, in short, in the hard basic facts of the human condition. For the ancient Greeks and Romans, myths were everywhere. [...]

Some of the flattening-down of the strangeness and violence of the characters of classical literature has doubtless been an understandable consequence of retelling the tales with children in mind. But the Greek myths shouldn't be thought of as children's stories – or just as children's stories. In some ways, they are the most grownup stories I know. In recent years there has been a blossoming of novels – among them Par Barker's The Silence of the Girls, Natalie Haynes's A Thousand Ships and Madeline Miller's Circe – that have placed female mythological characters at the centre of stories to which they have often been regarded as peripheral. [...] Once activated by a fresh imagination, the stories burst into fresh life.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Step 1

1

Pick out elements that make myths fantastical and grounded in reality, and classify them in two columns.

| Fantastical elements | Realistic elements |

|---|---|

2

According to the text, why shouldn't Greek myths be considered just children's stories?

3

How do modern retellings make these stories relevant today?

Action!

Go on the Internet and prepare a short presentation of a Greek myth. Focus on how it can echo an element of your daily life or a contemporary event.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

2Madeline Miller, giving voice to the silenced

Madeline Miller talks about writing Circe, 2019.

Vidéo associée

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Step 2

Watch the video.

1

Why did Madeline Miller initially keep her work a secret?

2

What groups of people does she want to give a voice to?

3

In what ways does she modernise the character of Circe?

Action!

Start thinking about your new retelling. Like Miller, who gives a voice to women, find a subject you would like to defend and support.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

3Wonder Woman, from myth to comics

Wonder Woman origin story from Greek mythology, 2023.

Vidéo associée

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Step 3

Before watching the video.

Watch the video.

1

What do you know about Wonder Woman? How would you link her to Greek mythology? Discuss it in groups.

Watch the video.

2

Pick out the places and characters. Then, create a family tree.

3

What are the differences between the story created by DC Comics and the real Greek myths?

Action!

Choose one character from Zeus's family and explain how you would modernise it.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Ready...

- Choose one famous figure of Greek mythology (they can be mortal or immortal).

Steady...

- Gather your ideas to modernise the corresponding myth: which cause do you want to defend? In which ways will it be modern?

Go!

- Write the pitch of a retelling of an ancient Greek myth.

Une erreur sur la page ? Une idée à proposer ?

Nos manuels sont collaboratifs, n'hésitez pas à nous en faire part.

j'ai une idée !

Oups, une coquille