Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

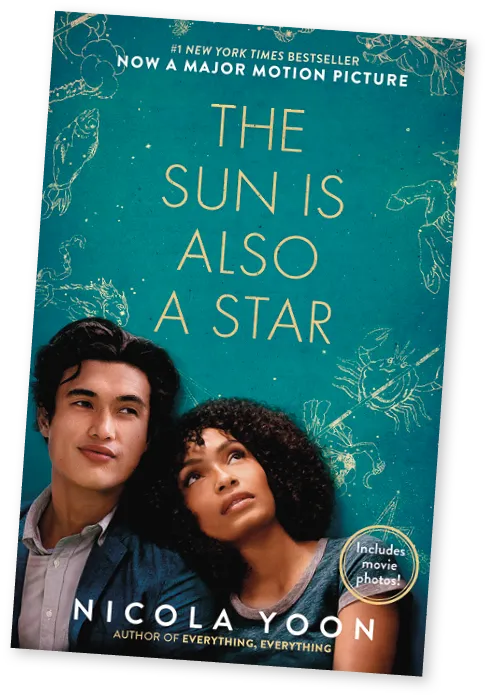

Published in 2016, Nicola Yoon's The Sun Is Also a Star is a young-adult

novel and National Book Award finalist. Told from multiple character

perspectives, the novel tells the story of Natasha, an undocumented

Jamaican Black girl on the day she meets Daniel, a middle-class, South

Korean immigrant whose family own a Black beauty supply store in

Harlem. The novel begins takes place in the span of one day, the last

one before Natasha's family are forced to leave the U.S.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Texte

The sun is also a star

Natasha

HARLEM IS ONLY A TWENTY-FIVE-MINUTE subway ride from where we were, but it's like we've gone to a different country. The skyscrapers have been replaced by small, closely packed stores with bright awnings. [...] Finally we stop in front of a black hair care and beauty supply store. It's called Black Hair Care. I've been into lots of these. “Go down the street to the beauty supply and pick up some relaxer for me,” says my mother every two

months or so. It's a thing. Everyone knows it's a thing how all the black hair care places are owned by Koreans and what an injustice that is. I don't know why I didn't think of it when Daniel said they owned a store. I can't see inside because the windows are covered with old, sun-faded posters of smiling and suited black women all with the same chemically treated hairstyle. Apparently — according to these posters, at least — only certain hairstyles are allowed to attend board meetings. Even my mom is guilty of this kind of sentiment. She wasn't happy when I decided to wear an Afro, saying that it isn't professional-looking. But I like my big Afro, I also liked when my hair was longer and relaxed. I'm happy to have choices. They're mine to make. [...]

Hair, an African American history

IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY AFRICAN CIVILIZATIONS, hairstyles were markers of identity. Hairstyle could indicate everything from tribe or family background to religion to social status. [...] That history was erased with the dawn of slavery. On slave ships, newly captured Africans were forcibly shaved in a profound act of dehumanization, an act that effectively severed the link between hair and cultural identity. Postslavery, African American hair took

on complex associations. “Good” hair was seen as anything closer to European standards of beauty. Good hair was straight and smooth. Curly, textured hair, the natural hair of many African Americans, was seen as bad. Straight hair was beautiful. Tightly curled hair was ugly. In the early 1900s, Madam C. J. Walker, an African American, became a millionaire by inventing and marketing hair care products to black women. [...]

The way African American women wear their hair has often been about much more than vanity. It's been about more than just an individual's notion of her own beauty. When Natasha decides to wear hers in an Afro, it's not because she's aware of all this history. She does it despite Patricia Kingsley's assertions that Afros make women look militant and unprofessional. Those assertions are rooted in fear — fear that her daughter will be harmed by a society that still so often fears blackness. Patricia also doesn't raise her other objection: Natasha's new hairstyle feels like a rejection. She's been relaxing her own hair all her life. She'd relaxed Natasha's since she was ten years old. These days when Patricia looks at her daughter, she doesn't see as much of herself reflected back as before, and it hurts. But of course, all teenagers do this. All teenagers separate from their parents. To grow up is to grow apart. It takes three years for Natasha's natural hair to grow in fully. She doesn't do it to make a political statement. In fact, she liked having her hair straight. In the future, she may make it straight again. She does it because she wants to try something new. She does it simply because it looks beautiful. [...]

Natasha

“Well, this is it. This is the store.”

“Want to show me around?” I ask to help distract him.

“Not much to see. First three aisles are for hair. Shampoo, conditioner, extensions, dyes, lots of chemical things I don't understand. Aisle three is makeup. Aisle four is equipment.”

He glances at his dad, but he's still busy.

“Do you need something?” he asks.

I touch my hair. “No, I —”

“I didn't mean a product. We have a fridge in the back with soda and stuff.”

“Sure,” I say. I like the idea of seeing behind the scenes. We walk down the hair dye aisle. All the boxes feature broadly smiling women with the most perfectly colored and styled hair. It's not hair dye being sold in these boxes, it's happiness. I stop in front of a group of boxes with brightly colored dyes and pick up a pink one. There's a very small, secret, impractical part of me that's always wanted pink hair. It takes Daniel a few seconds to realize that I've stopped walking.

“Pink?” he asks, when he sees the box in my hand. I wiggle it at him.

“Why not?”

“Doesn't seem like your style.” Of course he's completely right, but I hate that he thinks so. Am I too predictable and boring? I think back to the boy I saw when we entered the store. I bet he keeps everyone guessing.

“Shows how much you know,” I say. and pat my hair. His eyes follow my hand, and now I'm really self-conscious and hoping he's not going to ask to touch my hair or a bunch of dumb questions about it. Not that I don't want him to touch my hair, because I do — just not as a curiosity.

“I think you would look beautiful with a giant pink Afro.” he says.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

a) How is Harlem depicted?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

b) What is surprising about the owners of Black hair stores?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

c) Pick out the words showing hair diktat.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

d) What do the last lines reveal about that narrator?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

e) What story did hair tell in 15th century African civilizations?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

f) How did slave owners try to stifle Africans' identity?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

g) Explain the difference between “good” and “bad” hair.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

h) How did C. J. Walker become rich?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

i) Compare Natasha's and her mother's point of view on hair.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

j) How is Natasha's hair style just part of growing up?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

k) Pick out the words showing Natasha is uncomfortable.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

l) How do Natasha's last sentences illustrate hair prejudice?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Nicola Yoon grew up in Jamaica and Brooklyn, and lives in Los Angeles with her husband, the novelist David Yoon, and their daughter. She is the bestselling author of Everything, Everything and The Sun Is Also a Star. She received several prizes and is the first Black woman to hit #1 on the New York Times Young Adult Best Seller List. Two of her novels have been made into major motion pictures.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Act out a dialogue.

Natasha comes home after dyeing her hair. Imagine how her family, especially her mother, react to her pink Afro. Are they surprised, upset, curious? How does Natasha defend her bold decision? What arguments does she give? Do they finally understand and accept her choice?

Natasha comes home after dyeing her hair. Imagine how her family, especially her mother, react to her pink Afro. Are they surprised, upset, curious? How does Natasha defend her bold decision? What arguments does she give? Do they finally understand and accept her choice?

Cliquez pour accéder à un module d'enregistrement audio

Enregistreur audio

Une erreur sur la page ? Une idée à proposer ?

Nos manuels sont collaboratifs, n'hésitez pas à nous en faire part.

j'ai une idée !

Oups, une coquille