Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

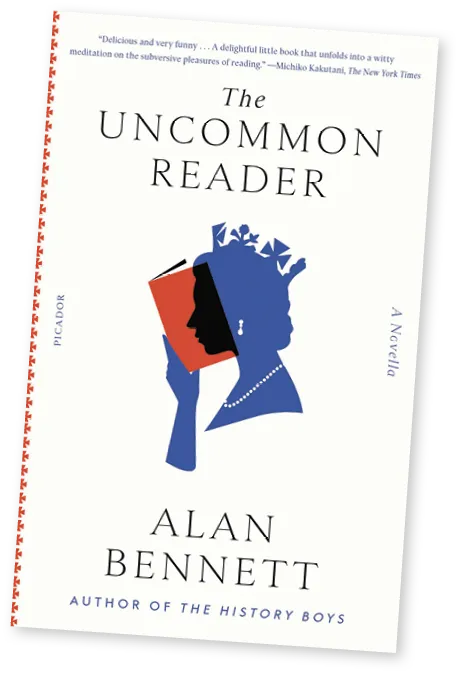

The Uncommon Reader is a novella which depicts Queen Elizabeth II unexpectedly

discovering a love for books. The more she reads, the more she becomes

interested in the world around her. Reading gradually changes her perspective and

she comes to question the prescribed order of the world. Through humour and

wit, Bennett explores how literature can change even the most powerful figures.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Texte

The Uncommon Reader

“It was the dogs' fault. They were snobs and ordinarily, having been in the garden,

would have gone up the front steps, where a footman generally opened them the door.

Today, though, for some reason they careered along the terrace, barking their heads off,

and scampered down the steps again and round the end along the side of the house,

where she could hear them yapping at something in one of the yards.

It was the City of Westminster travelling library, a large removal-like van parked next to the bins outside one of the kitchen doors. This wasn't a part of the palace she saw much of, and she had certainly never seen the library there before, nor presumably had the dogs, hence the din, so having failed in her attempt to calm them down she went up the little steps of the van in order to apologise.

The driver was sitting with his back to her, sticking a label on a book, the only seeming borrower a thin ginger-haired boy in white overalls crouched in the aisle reading. Neither of them took any notice of the new arrival, so she coughed and said, “I'm sorry about this awful racket,” whereupon the driver got up so suddenly he banged his head on the Reference section and the boy in the aisle scrambled to his feet and upset Photography and Fashion.

She put her head out of the door. “Shut up this minute, you silly creatures” – which, as had been the move's intention, gave the driver/ librarian time to compose himself and the boy to pick up the books.

“One has never seen you here before, Mr …”

“Hutchings, Your Majesty. Every Wednesday, ma'am.”

“Really? I never knew that. Have you come far?”

“Only from Westminster, ma'am.”

“And you are …?”

“Norman, ma'am. Seakins.”

“And where do you work?”

“In the kitchen, ma'am.”

“Oh. Do you have much time for reading?”

“Not really, ma'am.”

“I'm the same. Though now that one is here I suppose one ought to borrow a book.”

Mr Hutchings smiled helpfully.

“Is there anything you would recommend?”

“What does Your Majesty like?”

The Queen hesitated, because to tell the truth she wasn't sure. She'd never taken much interest in reading. She read, of course, as one did, but liking books was something she left to other people. It was a hobby and it was in the nature of her job that she didn't have hobbies. Jogging, growing roses, chess or rock-climbing, cake decoration, model aeroplanes. No. Hobbies involved preferences and preferences had to be avoided; preferences excluded people. One had no preferences. Her job was to take an interest, not to be interested herself. And besides, reading wasn't doing. She was a doer. So she gazed round the book-lined van and played for time. “Is one allowed to borrow a book? One doesn't have a ticket?”

“No problem,” said Mr Hutchings.

“One is a pensioner,” said the Queen, not that she was sure that it made a difference.

“Ma'am can borrow up to six books.”

“Six? Heavens!” […]

The Pursuit of Love turned out to be a fortunate choice and in its way a momentous one. Had Her Majesty gone for another duff read, an early George Eliot, say, or a late Henry James, novice reader that she was she might have been put off reading for good and there would be no story to tell. Books, she would have thought, were work.

As it was, with this one she soon became engrossed and, passing her bedroom that night clutching his hot water bottle, the duke heard her laugh out loud. He put his head round the door. “All right, old girl?”

“Of course. I'm reading.”

“Again?” And he went off, shaking his head.

The next morning she had a little sniffle and, having no engagements, stayed in bed saying she felt she might be getting flu. This was uncharacteristic and also not true; it was actually so she could get on with her book.

“The Queen as a slight cold” was what the nation was told, and what the Queen herself did not know, was that this was only the first of a series of accommodations, some of them far-reaching, that reading was going to involve.

It was the City of Westminster travelling library, a large removal-like van parked next to the bins outside one of the kitchen doors. This wasn't a part of the palace she saw much of, and she had certainly never seen the library there before, nor presumably had the dogs, hence the din, so having failed in her attempt to calm them down she went up the little steps of the van in order to apologise.

The driver was sitting with his back to her, sticking a label on a book, the only seeming borrower a thin ginger-haired boy in white overalls crouched in the aisle reading. Neither of them took any notice of the new arrival, so she coughed and said, “I'm sorry about this awful racket,” whereupon the driver got up so suddenly he banged his head on the Reference section and the boy in the aisle scrambled to his feet and upset Photography and Fashion.

She put her head out of the door. “Shut up this minute, you silly creatures” – which, as had been the move's intention, gave the driver/ librarian time to compose himself and the boy to pick up the books.

“One has never seen you here before, Mr …”

“Hutchings, Your Majesty. Every Wednesday, ma'am.”

“Really? I never knew that. Have you come far?”

“Only from Westminster, ma'am.”

“And you are …?”

“Norman, ma'am. Seakins.”

“And where do you work?”

“In the kitchen, ma'am.”

“Oh. Do you have much time for reading?”

“Not really, ma'am.”

“I'm the same. Though now that one is here I suppose one ought to borrow a book.”

Mr Hutchings smiled helpfully.

“Is there anything you would recommend?”

“What does Your Majesty like?”

The Queen hesitated, because to tell the truth she wasn't sure. She'd never taken much interest in reading. She read, of course, as one did, but liking books was something she left to other people. It was a hobby and it was in the nature of her job that she didn't have hobbies. Jogging, growing roses, chess or rock-climbing, cake decoration, model aeroplanes. No. Hobbies involved preferences and preferences had to be avoided; preferences excluded people. One had no preferences. Her job was to take an interest, not to be interested herself. And besides, reading wasn't doing. She was a doer. So she gazed round the book-lined van and played for time. “Is one allowed to borrow a book? One doesn't have a ticket?”

“No problem,” said Mr Hutchings.

“One is a pensioner,” said the Queen, not that she was sure that it made a difference.

“Ma'am can borrow up to six books.”

“Six? Heavens!” […]

The Pursuit of Love turned out to be a fortunate choice and in its way a momentous one. Had Her Majesty gone for another duff read, an early George Eliot, say, or a late Henry James, novice reader that she was she might have been put off reading for good and there would be no story to tell. Books, she would have thought, were work.

As it was, with this one she soon became engrossed and, passing her bedroom that night clutching his hot water bottle, the duke heard her laugh out loud. He put his head round the door. “All right, old girl?”

“Of course. I'm reading.”

“Again?” And he went off, shaking his head.

The next morning she had a little sniffle and, having no engagements, stayed in bed saying she felt she might be getting flu. This was uncharacteristic and also not true; it was actually so she could get on with her book.

“The Queen as a slight cold” was what the nation was told, and what the Queen herself did not know, was that this was only the first of a series of accommodations, some of them far-reaching, that reading was going to involve.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

a) Explain why the Queen had never noticed the library before.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

b) How does the driver react to the Queen's presence?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

c) Who are the silly creatures the Queen address?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

d) Identify the different characters talking and what they are saying.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

e) How is the Queen's

conversation with

Norman different from

her usual interactions?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

f) The Queen had never taken much interest in reading. Justify why by quoting the text.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

g) Why might having personal preferences be a problem for a monarch?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

h) How does the Queen refer to herself? Why?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

i) Who is the duke? Elaborate on his reaction upon hearing that the Queen is reading.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

j) What does the Queen's decision to stay in bed reveal?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Alan Bennett (born in 1934) is a British playwright, author, and actor

known for his sharp wit and keen observations of British society. His

works often explore themes of class, power, and tradition with humour

and irony. Originally a historian, he gained fame as a playwright with

Beyond the Fringe (1960), a satirical revue that challenged the British

establishment. His later works, including The Madness of George III (1991)

and The History Boys (2004), blend comedy with deeper social critique.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

A reading list for the Queen

You are a rebellious librarian with a rare chance to challenge the Queen's worldview through books. Choose a title that might shake her beliefs about power, duty, or modern life. Act out the dialogue. One student plays the Queen, resisting change, while the other passionately defends his/her book choices. Will you open Her Majesty's mind or will tradition prevail?

You are a rebellious librarian with a rare chance to challenge the Queen's worldview through books. Choose a title that might shake her beliefs about power, duty, or modern life. Act out the dialogue. One student plays the Queen, resisting change, while the other passionately defends his/her book choices. Will you open Her Majesty's mind or will tradition prevail?

Cliquez pour accéder à un module d'enregistrement audio

Enregistreur audio

Une erreur sur la page ? Une idée à proposer ?

Nos manuels sont collaboratifs, n'h�ésitez pas à nous en faire part.

j'ai une idée !

Oups, une coquille