Unit 14

Bac

Exam file

Préparation aux évaluations communes

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Évaluations communes

1H30Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

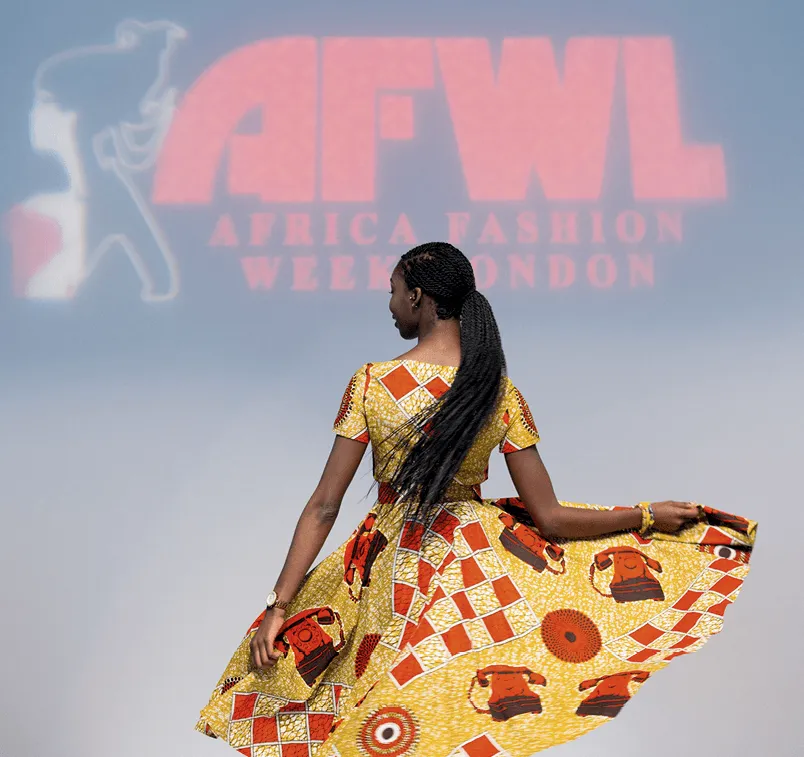

Compréhension de l'oral Fashioning the Future

1

Avant l'écoute, lisez le titre ci-dessus et regardez le nuage de motsa. Sur quoi peut porter cet enregistrement ? Faites trois hypothèses.

b. Trouvez cinq autres mots que vous pourriez entendre dans l'enregistrement.

2

Après l'écoute En rendant compte, en français, du document, vous montrerez que vous avez compris les éléments suivants :

- Le thème principal du document ;

- À qui s'adresse le document ;

- Le déroulement des faits, la situation, les événements, les informations ;

- L'identité des personnes ou des personnages et, éventuellement, les liens entre elles / entre eux ;

- Les éventuels différents points de vue ;

- Les éventuels éléments implicites du document ;

- La fonction et la portée du document (relater, informer, convaincre, critiquer, dénoncer, etc.).

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Business Incorporated: Liberian Designer Uses Fashion To Showcase Growth, Channels Television, 2016. (Timing: 03:20 to 05:50)

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Compréhension de l'écrit

Being African abroad: Are we a lost generation?

A few weeks ago, I was approached by an elderly Somali man who asked about my ethnicity. I responded that I was Somali. He then began to ask for help in Somali. As he described what he needed, I stood there blank-faced, staring at this man and trying to figure out how to explain to him that I could not understand Somali. I mean, yes I am Somali. But I do not speak the language.

When I finally mustered up the courage to tell him, a wave of frustration appeared on his face. He was dumbfounded. “You do not understand,” he said. “Your language is your passport. Without it, you are just a Somali by appearance and nothing else,” he protested rather poetically. I realised he made a very valid point. I truly had nothing that separated me from my fellow Canadian peers besides my skin complexion. I could not speak my language and the older I became the more I realised I had picked the ‘Westernised' card over the ‘embracing my ethnicity' card. It was time I found my roots.

Growing up, I was always the token black kid in most of my classes. I had the darkest skin, the roughest hair. It was nothing drastic, but I was still bullied or stereotyped by my peers and teachers. However, over time, I learned to adapt. Like a turtle, I mastered the ability to live both in water and on land. Or, I should say, I learned to survive at home and outside of my home. [...] To me, fitting in was entirely different from belonging. [...] Being Westernised seemed ideal. [...] The reality was that Westernised values collided with my traditional Somali values.

A “double identity” was not easy to achieve. My parents were traditional Somalis living in Toronto; my peers were all Canadians [...]. I highly doubt my parents or parents of other second-generation children would imagine that their kids would be put in a situation where they would have to deal with the clashing of values. As I grew older, I began to witness the extremes: some second-generation children began rejecting their culture or even effectively removing themselves from interaction with members of that culture just to avoid the stigmatisation of being associated with their nationality. Others began to develop a heightened sense of ethnic pride, often in reaction to discrimination or hostility from the host society. Either way, both seemed drastic to me.

The manner in which Somali youths, or even second-generation African youths, understand their identity is complex. The majority of second-generation Somalis struggle with the notion of identity simply because identity and culture are deeply intertwined – as religion is an identity, and nationality is an identity, and so on. It seems as though rather than incorporating various aspects of both the Western culture and our traditional culture, the majority of Somalis seem to have lost the overall Somali culture in their process of attempting to assimilate into society. There are more of us, who are unable to speak the language, or who do not generally uphold our cultural values.

We tend to forget that we are the future of our cultures. We are the ones who will carry forward our language, and our traditions. However, if we are too busy attempting to assimilate into a society that essentially rejects us, who will continue to keep our traditions alive? I would like to think there is hope. We have a chance to change our situation. Rather than suppressing one's identity, I feel as though it is time we began embracing the variety of identities.

When I finally mustered up the courage to tell him, a wave of frustration appeared on his face. He was dumbfounded. “You do not understand,” he said. “Your language is your passport. Without it, you are just a Somali by appearance and nothing else,” he protested rather poetically. I realised he made a very valid point. I truly had nothing that separated me from my fellow Canadian peers besides my skin complexion. I could not speak my language and the older I became the more I realised I had picked the ‘Westernised' card over the ‘embracing my ethnicity' card. It was time I found my roots.

Growing up, I was always the token black kid in most of my classes. I had the darkest skin, the roughest hair. It was nothing drastic, but I was still bullied or stereotyped by my peers and teachers. However, over time, I learned to adapt. Like a turtle, I mastered the ability to live both in water and on land. Or, I should say, I learned to survive at home and outside of my home. [...] To me, fitting in was entirely different from belonging. [...] Being Westernised seemed ideal. [...] The reality was that Westernised values collided with my traditional Somali values.

A “double identity” was not easy to achieve. My parents were traditional Somalis living in Toronto; my peers were all Canadians [...]. I highly doubt my parents or parents of other second-generation children would imagine that their kids would be put in a situation where they would have to deal with the clashing of values. As I grew older, I began to witness the extremes: some second-generation children began rejecting their culture or even effectively removing themselves from interaction with members of that culture just to avoid the stigmatisation of being associated with their nationality. Others began to develop a heightened sense of ethnic pride, often in reaction to discrimination or hostility from the host society. Either way, both seemed drastic to me.

The manner in which Somali youths, or even second-generation African youths, understand their identity is complex. The majority of second-generation Somalis struggle with the notion of identity simply because identity and culture are deeply intertwined – as religion is an identity, and nationality is an identity, and so on. It seems as though rather than incorporating various aspects of both the Western culture and our traditional culture, the majority of Somalis seem to have lost the overall Somali culture in their process of attempting to assimilate into society. There are more of us, who are unable to speak the language, or who do not generally uphold our cultural values.

We tend to forget that we are the future of our cultures. We are the ones who will carry forward our language, and our traditions. However, if we are too busy attempting to assimilate into a society that essentially rejects us, who will continue to keep our traditions alive? I would like to think there is hope. We have a chance to change our situation. Rather than suppressing one's identity, I feel as though it is time we began embracing the variety of identities.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Questions

a) What do you learn about the narrator?

b) Pick out the adjectives related to feelings in the second paragraph. How does the narrator feel?

c) What impact did the man‘s reaction have on the narrator in the second paragraph?

d) Pick out the contrast presented in the fourth paragraph. How did the second generation adapt, according to the author?

e) Did the narrator see her double culture as an advantage? Why or why not?

f) Pick out the positive vocabulary from the text. What are the narrator's hopes for the future?

b) Pick out the adjectives related to feelings in the second paragraph. How does the narrator feel?

c) What impact did the man‘s reaction have on the narrator in the second paragraph?

d) Pick out the contrast presented in the fourth paragraph. How did the second generation adapt, according to the author?

e) Did the narrator see her double culture as an advantage? Why or why not?

f) Pick out the positive vocabulary from the text. What are the narrator's hopes for the future?

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Expression écrite

Choisissez un sujet et répondez-y en anglais en 120 mots minimum.

“Your language is your passport.” – Iman Hassan.

Use this quote to write a post on a social network and express your point of view.

Should anyone choose between embracing their ethnicity and cultural legacy or being a westernised global citizen? Why?

Sujet A - Texte

“Your language is your passport.” – Iman Hassan.

Use this quote to write a post on a social network and express your point of view.

Sujet B - Texte - Vidéo

Should anyone choose between embracing their ethnicity and cultural legacy or being a westernised global citizen? Why?

Sujet C - Vidéo

You react to the video and say what actions it inspires you to do.

Ressource affichée de l'autre côté.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

Faites défiler pour voir la suite.

- Assurez-vous d'utiliser les champs lexicaux rencontrés au cours de cette unité.

- Donnez votre avis et argumentez en utilisant des informations précises et pertinentes ainsi que des exemples.

- Vérifiez plusieurs fois votre syntaxe et votre orthographe !

Une erreur sur la page ? Une idée à proposer ?

Nos manuels sont collaboratifs, n'hésitez pas à nous en faire part.

j'ai une idée !

Oups, une coquille